Sarah Campbell, Curator, Central Saint Martins Museum & Study Collection

This article calls for a greater use of play in university museums and study collections. Play is not new in museums but ‘ludic practice’ calls for a tailored approach, centred on teaching collections and art and design students, and focusing on the object rather than the game or play interaction, as can be the focus in public collections. This article explores the work of Carson & Miller, the development of ludic practice and gives an overview of initial teaching experiments carried out with first year students on the Fine Art 3D pathway at Central Saint Martins (UAL).

ludic; museums; collections; object-based learning

The Central Saint Martins Museum & Study Collection began using ‘ludic practice’ as a strategy for engaging students and visitors in 2017. The term ‘ludic practice’ relates to object-led games and play taking place in a museum collection, and in this context, I settled on the term to sum up the playful but considered approach I wished to explore. The development of these practices grew out of conversations with the artist duo, Carson & Miller. Jonathan Carson is Associate Dean of Student Experience at Central Saint Martins and Rosie Miller is Director of Art and Design at the University of Salford, Manchester. Carson & Miller use collections as the art materials in their practice, as conduits to explore the people inside and outside collections, and the world of collecting itself. Ludic practice in this context relates more to teaching than as a standalone art form, and seeks to encourage curators and collections managers to be more playful in their use of collections for the benefit of art and design students.

Conversations with Carson & Miller along with other museum professionals – including Kerry Watson, Librarian Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Neil Lebeter, Special Collections University of Edinburgh, Stephanie Boydell, Curator, Manchester Metropolitan University Special Collections – have revealed that it is possible to be more playful with museum objects. These conversations have refreshed my approaches to teaching in the CSM Museum and enforced the idea that we should be taking more risks with how we use our objects and how we teach with them.

A key part of how we work in the CSM Museum is our focus on the importance of touch to our students. Handling museum objects can give students a tangible level of excitement and allow them to glean information from objects first hand. The trust we place in them also makes this teaching experience special and different to many of the other interactions they will have. Through ludic practice, games and play will feed into and support this engagement with objects as well as offering new types of interaction.

University art museums are places for questions. They are laboratories, places to provoke and experiment (Hammond et al., 2006, p.22). Museum collections and archives are key assets to universities and our art and design collection, and many others in the country, are places were teaching can take place with real ‘museum quality’ artefacts. As this article will explore, ludic practice is a new way of provoking reactions in students and visitors. It is a call for greater and more tailored use of play in university art and design collections. Play is not a new idea in museums. However, the games created in public museums can often be overly focused on the interaction rather than the object, and aim to work with a wide ranging, unsupervised audience. Ludic practice differs is in its selective implementation and adaption of games and play for the specific environment of the university collection and its audience. Due to their association with institutions of learning as well as research, they are places that facilitate a more active pedagogic experiment and innovative use of collections. In addition, as is the case with the Central Saint Martins (CSM) Museum & Study Collection, we often work closely with art and design students, whose nuanced and surprising interactions with objects mean that they need to be supported as well as challenged.

Although I am not an academic and the work that informs this article has been led by experience, I none-the-less believe that by being more playful in our holdings we can encourage rich interactions and interpretations of collections that have specific benefits to our students and our collections.

The use of games, or play, adapted specifically for the university teaching collection environment, to be used in any aspect of teaching collection practice e.g. teaching, exhibition, lecture or online.

Games and play in ludic practice must be object-led and involve spontaneous or undirected involvement from participants.

(Campbell, 2019)

I have chosen to use the term ‘ludic’ rather than ‘game’ or ‘play’. This is because the latter terms have associations with children’s education or the theory of games, neither of which relate to this new way of working. I wanted a grown-up term that was an equivalent but with key differences. The word ‘ludic’ means to show spontaneous or undirected playfulness, which are precisely what this approach seeks to encourage. The words ‘undirected’ and ‘spontaneous’ indicate the light-handed and playful engagements it aims to create and allows the opportunity to explore the world of the unconscious as found in games of the Surrealists.

I would also credit Object Based Learning (OBL) (Prown, 1982) as an influence on ludic practice. OBL is a methodology used to promote deep readings of museum or cultural objects by students and visitors by interaction with the object alone. It attempts to give greater agency to the participant and results in a wider variety of readings and interpretations of an object than would traditionally exist in a museum. Having taught OBL for several years, I have seen the conversations it sparks, acting as a conduit between students and object, which is something I want to echo in ludic practice. OBL methodology has given students confidence in approaching museum objects, enabling them to have more agency in the museum environment. I see ludic practice as something that sits alongside and supports these activities.

Carson & Miller have reminded me of the importance of understanding how artists use collections. They are unencumbered by the practical issues of looking after a collection and they are not blinded by over familiarity to the objects with in it, rather, they have the ability to see collections afresh (as our students do) and can correlate collections to other areas. As curators we are always trying to think of new ways to curate and teach with the collection but we find co-curating and co-teaching with other departments very rewarding. Similarly, talking to Carson & Miller refreshed my views on our collection and how we use it, as I attempted to think more like an artist in my role as a curator.

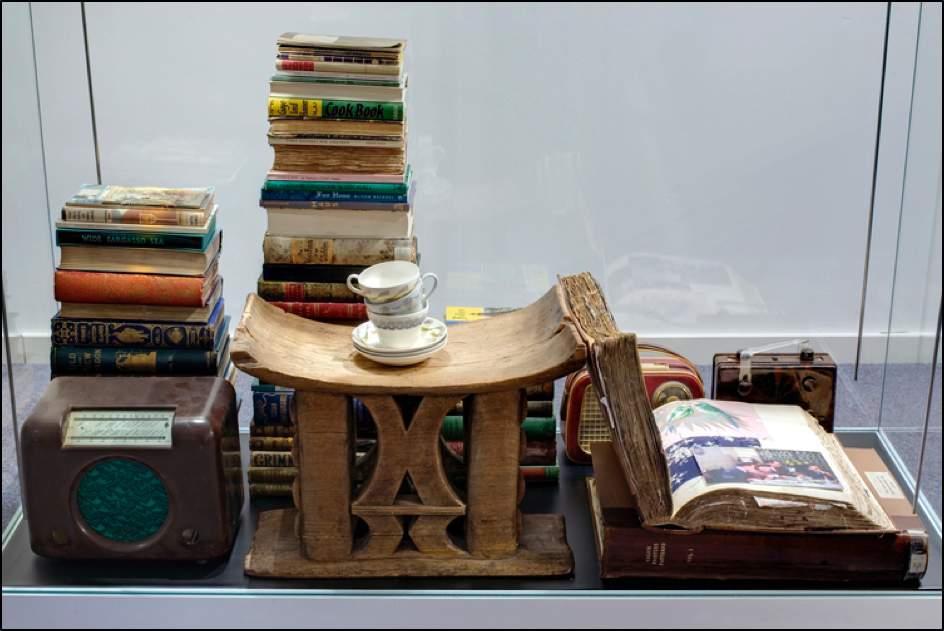

One way in which they refreshed collections was through display. At their Manchester Metropolitan University exhibition The Story of Things (Carson & Miller, 2019a) objects from the university’s special collections were piled up, with books in columns, ceramics in stacks, and objects sat inside other artefacts. This is not how we would automatically display objects, as it is not always best practice to have objects leaning on each other or being stacked in any kind of precarious way. However, the display created an instant visual juxtaposition, forcing visitors (and museum staff) to re-assess these coalescing objects – of different times, places and textures and was well worth the risk. By physically imposing on one another, by being stacked and brought into physical contact with each other, the items sparked new conversations on material, social and cultural levels. The objects were never in danger, but the fact that artists were responding to the collection and new playful links were being made, meant it was worth the collection curator trialling new display methods to make it work.

In 2015, Carson & Miller played with several collections at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art including the library of surrealist artist and critic Roland Penrose and the re-created studio of artist Eduardo Paolozzi (Carson & Miller, 2019a). Carson & Miller used the Penrose library for a game using books. All the books had their spines turned to the wall and members of the public chose which ones interested them, based upon their appearance and ‘object-ness’ alone. They could examine the object up close (which often sparked conversations and shared knowledge by the curatorial team and public) and the books where collated on another shelf, now turned round the right way with the spines facing outward. In the Paolozzi studio, for a separate game, Jonathan Carson sat on the edge of Paolozzi’s mezzanine bed (see Figure 3 below), in a room which is filled with original archival material, and played a ‘Game of Things’ with the visitors. Objects representing letters A-Z were selected by the public in a game of ‘eye-spy’ from the studio. Once selected they were removed by staff and brought from the studio into a vitrine in the public gallery.

These games were part of large project at the SNGMA and would be too big a project to attempt in a small museum without additional funding but there is a lot we can learn from them. The principles behind their work that could be applied to a collection like ours at CSM where all our items are kept in onsite stores and teaching mostly takes place in our study room (known as a reserve collection). For example, instead of standing in Paolozzi’s studio at the SNGMA, we might be able to take a student into the stores to select an object for a group session. Or instead of bringing Paolozzi’s artefacts out of the re-created studio like Carson & Miller did, we could use objects from an exhibition that was being de-installed. Students could select from a selection of transitional objects and opt to take a closer look, or a randomised selection could be made by students through a game. The reversed book idea could be done on one shelf of a storeroom, or books could be assigned numbers for students to pick out of a hat. Not all the ideas in ludic practice have to be as ambitious as Carson & Miller’s but there is a lot to learn from their approach, and the compromises we discussed were never the less exciting.

Carson & Miller’s use of collections is unusual and provocative. They disrupt and explore the structure, both physical and administrative, of the museum or archive and that provocation of collections is a good thing to explore. We need to question why we do things in certain ways and try and find time to be more inventive in the teaching and curating we do with our collection.

From my first meeting with Jonathan Carson I began to think of how we could play games with our collection. Conversations with Carson & Miller’s sometime academic collaborator Dr Patricia Allmer (2018) led to an exploration of how surrealist artists used play to create artworks. In this art movement from the early twentieth-century, I found a ready-made source of ideas to adapt, usefully listed in A Book of Surrealist Games by Alistair Brotchie and Mel Gooding (1995). Like Carson & Miller, they provide an artistic lens to observe objects and approaches to creative thinking. This movement also influenced the decision to use the word ‘ludic’ rather than play. The ‘undirected’ nature of play is reflected in the Surrealist artists’ interest in the unconscious. An unmediated or freeform connection to objects seemed an appealing aim, and I felt an element of the surreal should be encouraged in ludic practice.

As well as the games of the surrealists, I also wanted to adapt other existing games for museum use, such as the card game ‘Snap’ or Dominoes. The reasoning behind this was that I wanted concepts that people were familiar with, so that the museum teaching activities were simpler to understand. I may well develop brand new games in the future, but this initial set of adapted and surreal games have provided a good starting point.

The first group I taught ludic practice were in the first year of BA Fine Art 3D pathway, run by Elizabeth Wright. Over the past few years, I have taught various museum sessions with the first years on this course, and I felt that students at this stage of their studies might benefit from experimenting with ludic practice. The students were already used to the idea of playing games in their seminars as the first year is all about breaking down the students idea of themselves as artists and getting them to collaborate and become more inquisitive and questioning of their practice. Students had worked in groups creating rules for making artworks and had altered and added to other people’s work as part of that process. The games I suggested were in line with this way of thinking, designed to play with the idea of rules and possibly leaving a trace of the game that could be used a rules to create other artworks.

In the traditional game of Dominoes, small blocks are connected to each other by matching-up the numbers/configurations of dots at either end. Taking this concept forward, I replaced domino blocks with museum objects, asking students to create and match up connections between them. The objects had no apparent connection, ranging from nineteenth-century Japanese prints to papier-mâché covered cowboy boots from 2017.

The group of 30 students were split into two groups of 15, which were asked to link six items together. They were asked to draw or note these connections on a large piece of paper, upon which the objects were placed. The full list of objects were as follows – Group 1 had a Sex Pistols plaque, Japanese slipper socks, a condom pot, 1930s fabric samples, a herbal book, and a black and white etching of oust houses from the 1920s. Group 2 had contemporary cowboy boots, a ‘hamster’ paper shredder, a photo of early work by Alexander McQueen, a scrapbook of wine labels, a Japanese print c.1850 and a bedside air diffuser.

I selected an initial object to start of the game for each group. After that, it was up to them to decide what object came next and how to connect them. Once they had connected all the objects and recorded the connections, the objects were taken away and they were left with a group ‘drawing’ of the connections. These connections, or instructions, or rules, where then used to influence or create an artwork made by the groups.

In my experience of delivering games to different groups, I believe the students found Dominoes the most challenging. Some said that it would have been more approachable if all the objects had an apparent connection at first, more like actual Domino blocks, so that the connections they made were from a smaller pool, rather than being faced with a huge variety of options. I think working in smaller groups would also have yielded better interactions but nevertheless the end result was interesting.

At the CSM Museum, we do not typically allow students to draw very near or around objects. Due to the size of the paper, the objects and students were all working on the floor, which is also something we had not done before (students usually work at large tables). This changed the way the students approached and handled the objects, as they were sat next to them. These may sound like small things, but they had a significant effect on the atmosphere. Moving the objects further away from the structures of the museum ‘study room’ and into an environment that resembles a creative studio is a risk, particularly when working with sometimes fragile archive materials, but this transition made the objects feel more alive, enabling them to become part of the students’ working process.

Taken from the card game of the same name, this next activity involved splitting up the group of 30 or so students into groups of four to six. Each group had an object on a table. Every person in the group had to write down answers to various questions posed by me about the object, listing and/or noting down equivalent ‘things’ or concepts to the object they had. These questions, or prompts included:

In the same way that you match up different suits or colours in a game of Snap, playing with cards, I wanted the students to think of equivalents for the museum objects, taken from their own experience. The idea being that everyone would have a different equivalent for an object, even if they had never encountered it before.

Forcing the students to think of equivalents, as well as the uses and environments associated with a range of odd objects (which included rubber salt and pepper shakers, a 1970s wallpaper book, and a fifteenth-century illuminated manuscript) provoked a range of responses, only some of which are usually promoted by the type of questioning that happens in object based learning. I was worried about this at first, as we were doing an object based learning task too but this actually worked out very well. It highlighted the importance of the structure of OBL (describing, deducting, hypothesising) (Prown, 1982) as being very different to the more loose and creative task of coming up with a range of equivalents for a new object.

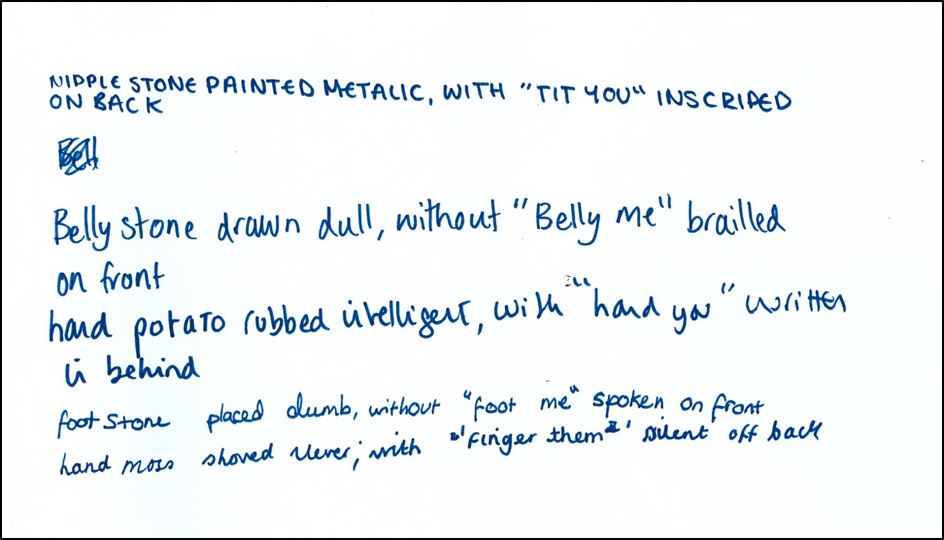

Taken from a surrealist game with the same name, Opposites was the most successful of the ludic activities. This is a writing game, where students sit in groups (the same ones we used for the game of Snap), but only one person per table was shown the object. That person then writes a short line of text describing the object. The objects included a piece of jewellery by Hollie Paxton, 2 medals from the art medal project collection, a black and white etching by Claire Leighton, box of black and white photographs showing the typographer Edward Johnston’s teaching material written up on blackboards. The next person, who has not seen the object, writes the opposite of this line of text, then folds over and hides the line they respond to, before handing it to the next person. The idea being that each person writes the opposite of the previous person. The end result is revealed once all participants have added to the list (much like in another game called Consequences).

The game produced blocks of text which resembled artistic works known as ‘concrete poetry’ which were all based on, but removed from, a museum object. The positive and negative descriptions often hit the mark or revealed characteristics of the object that the other players of the game could not have known. For one object – a bronze medal cast from a human nipple – players mistook, described or associated it with various different parts of the body. For that group the opposite of one body part was another body part. The use of language in each group varied greatly. Many words do not have an obvious antithesis which allowed for greater freedom of interpretation. During a ‘crit’ of the work produced from these games, which took place a week later, the Opposites game was mentioned as the most interesting by the students. As one student said ‘it certainly made me look at the objects in a different way’ (3D pathway Fine Art student, 2018). Students also described how the object itself is not always immediately engaging to a student, observing that the parallel conversations about it (which are set-up by ludic practice), are a way for them to connect with the museum. Producing text in that way and creating undirected interpretations of the objects was a successful way to engage students with objects. It gave them greater agency in the museum context as they had developed their own connections to objects and created a cloud of extra knowledge around them based on their own experience rather than a prescribed history.

Although my initial experiments with ludic practice put the object at the heart of the activity, I may not have thought enough about the part touch plays in this and how it could be utilised. Both Dominoes and Snap were visually led, but they could also be haptic-led, focusing on the importance of touch rather than sight. Creating a list of questions based on non-visual senses could be an interesting way of coming up with richer sensory equivalents for the museum objects. We currently include smell in our OBL exercises, which always throws up interesting results. Touch based versions of my initial games, or new games focusing on haptic interactions, could be the next step to explore in developing ludic practice.

The potentials of ludic practice are exciting. As a curator working with a collection in an educational context using games and play to invent new teaching activities has been great way to refresh my practice. It is all too easy to form habits in teaching and curating, and time and resource pressures can make experimenting seem like an overwhelming task. Ludic practice is in its early days, but I believe play has a place in university collections. Ludic practice is a practical, tactile and grown-up approach to collections, offering realistic ways to play with museum objects that benefit students and collections. Museum curators like myself have the responsibility to look after the collection and educate people about it, we not artists nor designers, but we can be inspired by them and interpret what they need, by adapting how we approach our teaching. It is a difficult thing to do, but worth the challenge.

Another area where ludic practice may be of benefit is wellbeing. Just as games and play can be adapted for the benefit of art and design students in a teaching collection, external groups specialising in mental health wellbeing also have specific needs, which could be met by specially designed ludic practice activities.

The CSM Museum & Study Collection have worked with external groups, in the field of ‘social prescribing’ and now delivers wellbeing-oriented sessions in our annual teaching programme. Currently we combine a short ‘show and tell’ style session with a related making activity, usually headed by a student ambassador. We have generally found participants find both elements engaging, particularly the making, and activities that create ‘flow’ (Csikszentmihalyi, 2008), such as games that require concentration. ‘Flow state’ is the psychological term for ‘being in the zone’, being so immersed and engaged with an activity that you don’t notice other things around you, like time passing.

The point of ludic practice is that it is adaptable for different groups and needs, inside and outside the college. It has no set form, instead it is a more general philosophy of playfulness in museums that can be adapted to any group or requirement. Ludic practice is a way to give more agency to our students and visitors and to excite interactions with our collections, infusing a dose of the unexpected and playful.

3D pathway Fine Art student (2018) Interviewed by Sarah Campbell, 29 October.

Allmer, P. (2018) Interviewed by Sarah Campbell, 26 February 2018.

Brotchie, A. and Gooding, M. (1995) A book of surrealist games. Boston: Shambhala Redstone Editions.

Carson and Miller (2019a) ‘Images’, Carson & Miller. Available at: http://carsonandmiller.co.uk/images/#/the-story-of-things-1/ (Accessed: 1 March 2019).

Carson and Miller (2019b) ‘Game playing’, Carson & Miller. Available at: http://carsonandmiller.co.uk/game-playing/#/a-library-game/ (Accessed: 1 March 2019).

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2008) Finding flow. New York: Basic Books.

Hammond, A., Berry, I., Conkelton, S., Corwin, S., Franks, P., Hart, K., Lynch-McWhite, W., Reeve, C. and Stomberg, J. (2006) ‘The role of the university art museum and gallery’, Art Journal, 65(3), pp.20–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043249.2006.10791213.

Prown, J.D. (1982) ‘Mind in matter: an introduction to material culture theory and method’, Winterthur Portfolio, 17(1), pp.1–19. https://doi.org/10.1086/496065.

Sarah Campbell is a Curator at the Central Saint Martins Museum & Study Collection (UAL). She has 10 years of experience working in museums and collections. Her background is in History of Art, specialising in 20th Century British Modernism and within the CSM Museum she mainly works with the Contemporary Collection, Painting and Ceramics. Sarah has a research interest in ludic practice (games and play in museums) which developed out of her research on object based learning for her Postgraduate Certificate in Higher Education. Her role at CSM includes collections management, exhibition curating and teaching. She works with a variety of courses across CSM.